The artist of a diptych creates a two-panel work. The pieces are both separate and intrinsically linked. Conversing with one another, the images tell a story.

Now living in a city of artists, I’m finding the diptych instructive in how to experience place, a central theme in this Substack and my related photography website. Reflecting further, I’m also finding metaphors and parallels applicable to ongoing debates about land use and the built environment.

In my musings about New Mexico, I’ve found a land of juxtapositions, including diptychs.

Some examples of sudden, dramatic pairings and contrasts include: Light and shadow, deluge and drought, and violent skies juxtaposed with ground-level stillness. The monsoon season—the region’s defining summer drama—enhances these dualities. Thunderheads yield to a golden, serene light—a renewed landscape.

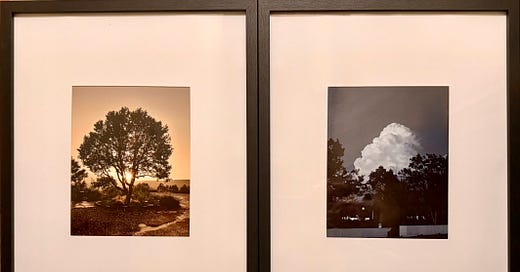

As part of my immersion in Santa Fe, I captured two panels from the same monsoon story this week. I’ve framed them side-by-side, as a personal diptych of my second Santa Fe summer.

On the right is a cumulonimbus, the heart of the storm.

On the left is the storm’s aftermath, 12 miles away. The ground glistens, and a well-rooted juniper contrasts with the late-day light, contributing to the tranquility which flows from the storm.

I believe that this diptych is more than an artist’s method or a meteorological interlude. It is also a holistic metaphor for how we work to shape built environments into resilient cities and places.

Professionals, policy advocates, conviction-based politicians, and community activists focus on various levels of placemaking and livability mechanics. They debate the merits of accessory dwelling units (ADUs), fighting to eliminate outdated parking minimums, questioning arbitrary square footage minimums, and advocating for more responsive and flexible zoning.

Just as critical is first assuring an understanding of a fundamental, underlying rhythm of a place by adapting the diptych of storm and stillness.

Why? Suppose we focus solely on equity and sustainability-driven buzzwords without a deeper understanding of their meaning. In that case, we risk lacking a contextual understanding of the underlying environments, landscapes, and cultures that shape them, and our solutions will be incomplete.

So, we need to understand the juniper as much as we need to understand the comprehensive plan and zoning code.

The disruption and renewal of a storm, and the image of the resilient tree, parallel economic crises, the housing shortage, and the sudden pressure that demands we adapt. Our policy responses—the ADUs, the zoning reform—are constructive solutions that aim to ensure societal storms nourish the ground rather than wash it away.

Living in Santa Fe sharpens this perspective—nearby physical landscapes are places of extremes. There is a skill in learning to read the sky and understanding that fierce, dramatic storms usually yield to ongoing resilience. In a city undergoing comprehensive plan and zoning updates, the metaphor is omnipresent. How can a neighborhood respect the flow of water during a monsoon? How can we design housing that balances the need for shelter from the storm with a connection to the light that follows?

Adherence to the distinctive Santa Fe Style may not always be the answer.

This diptych—framed this morning—will soon grace my wall (or someone else’s). It both fits my immersion goals and resurgence theme. It reminds me of the cyclical nature of resilience and resurgence.

The story of the thunderhead and the tree reminds me that place-building requires fluency in at least two languages: the technical language of policy and the fundamental, embedded language of place. For both, the diptych reminds us that there is not only the storm, but also what comes after.