Almost 50 years ago I wrote an opinion piece for the University of Washington Daily about a visit to Southern California and the ambiguous relationship that a Pacific Northwest kid had with freeways, sprawl, and Hollywood glitz.

I suppose this is an update, writing through filters of age, education, and experience, in search of how things have changed—simply and sincerely. More importantly, thanks to Gena (who was born about the time I wrote that Daily piece), it’s a reminder that Venice, California is more than the caricature-of-itself, sight-to-see menu item that is Venice Beach.

Gena (say Jenna, please) is a recovering lawyer like me—and at one point we even worked on similar environmental matters. An Obama administration veteran, I’ve been impressed at how she has reshaped her life to help others entering new chapters in their stories and leading by example in doing so.

I was also flattered how—knowing a little bit about my interests—she took the time last week to remind me of Marco, Amoroso, and Nowita, among the “walk-streets” of the Venice allure.

Our Tuesday morning conversation was ideal for a flâneur’s stroll, and not something I could have addressed in my student newspaper missive of so long ago. We discussed the classic assumptions about Los Angeles sprawl versus the community character of its particular municipalities—such as Venice—and the “microneighborhoods” (such as the increasingly pricey Oakwood and Silver Triangle) within them.

Challenging the Narrative

There is nothing too new and profound here, but it was an opportunity to adapt my learning from the City of London and its 32 boroughs and places like them. A uniform narrative about large urban settlements disregards the contextual identities of a city’s constituent communities. Venice, as is readily readable from its bohemian beachfront, historic charm, and modern challenges, is no stranger to the diversity and adaptability of urban life.

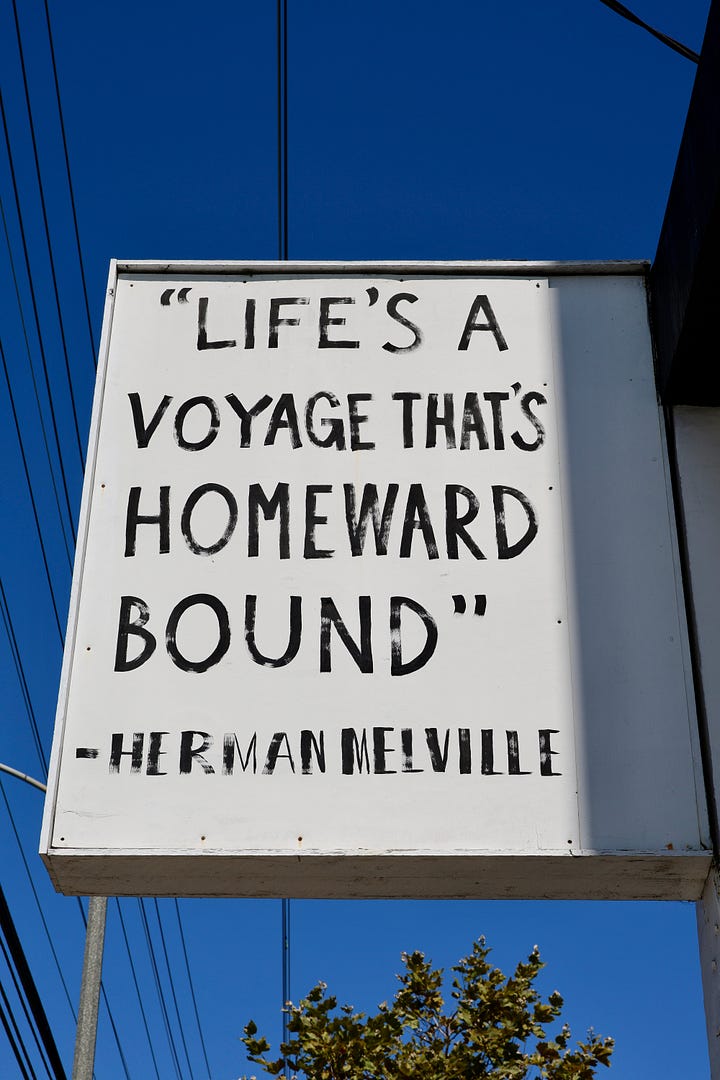

In particular, Venice still offers a counter-narrative to freeways, sprawl and suburban stereotypes—or perhaps it is more correct to say it coexists among them. Compact, walkable streets and community spaces communicate close-knit neighborhoods and a merger of development with cultural and natural features.

Needless to say in this day and age: gentrification and homelessness are part of the mix, as well.

Venice’s Walk-Streets

Venice’s walk-streets are a network of pedestrian pathways that fan out from the beach. They showcase a mixture of greenery and older homes over and above the nearby and better-known play on the canals of Venice, Italy.

The father of the American Venice, Abbot Kinney, designed the walk-streets—including Marco Place, Amoroso Place, and Nowita Place—in the early 1900s as part of his vision to create a more connected community. The paths still communicate a blend of old and new distinctly set off from an autocentric world.

One particularly memorable spot was a tree in a Marco Place open area that Gena joked could be an outdoor “office” to take calls. Such a spontaneous natural workspace shows the tranquility we can find when we need it—a vignette of adapting a public microenvironment to suit needs and lifestyles with the Santa Monica Freeway not too far away.

Potentials

If I were a bit more reflective in 1977, I could have written much of this piece then. But I had a more simplistic view of Los Angeles as a sprawling, homogeneous city with a vibe that literally dominated the airwaves.

Now, it’s stories and experiences that are more important—including a spontaneous office in a walk-street and a kind invitation to share ideas about the endless possibilities of what comes next.

Venice has really changed over the years. But the core of the spirit is still the same. And I think this is often shown in the way the city evolve. Thanks for sharing Gena’s and your story here, Chuck.