Five years after the pandemic began, I remember London during the disorienting, enforced stillness of 2020. I spent time walking between boroughs and exploring transitions between them. One pastime was finding solace in seeing how public health emergencies had happened before.

The city became a masterclass for an expat immersed in how “this too shall pass.” Popularized by Abraham Lincoln and Edward Fitzgerald, “This too shall pass” has more ancient roots, likely as a Persian fable about a ring with a message that would cause happiness when sad and sadness when happy. A comforting phrase can haunt us and make us wonder what could come next.

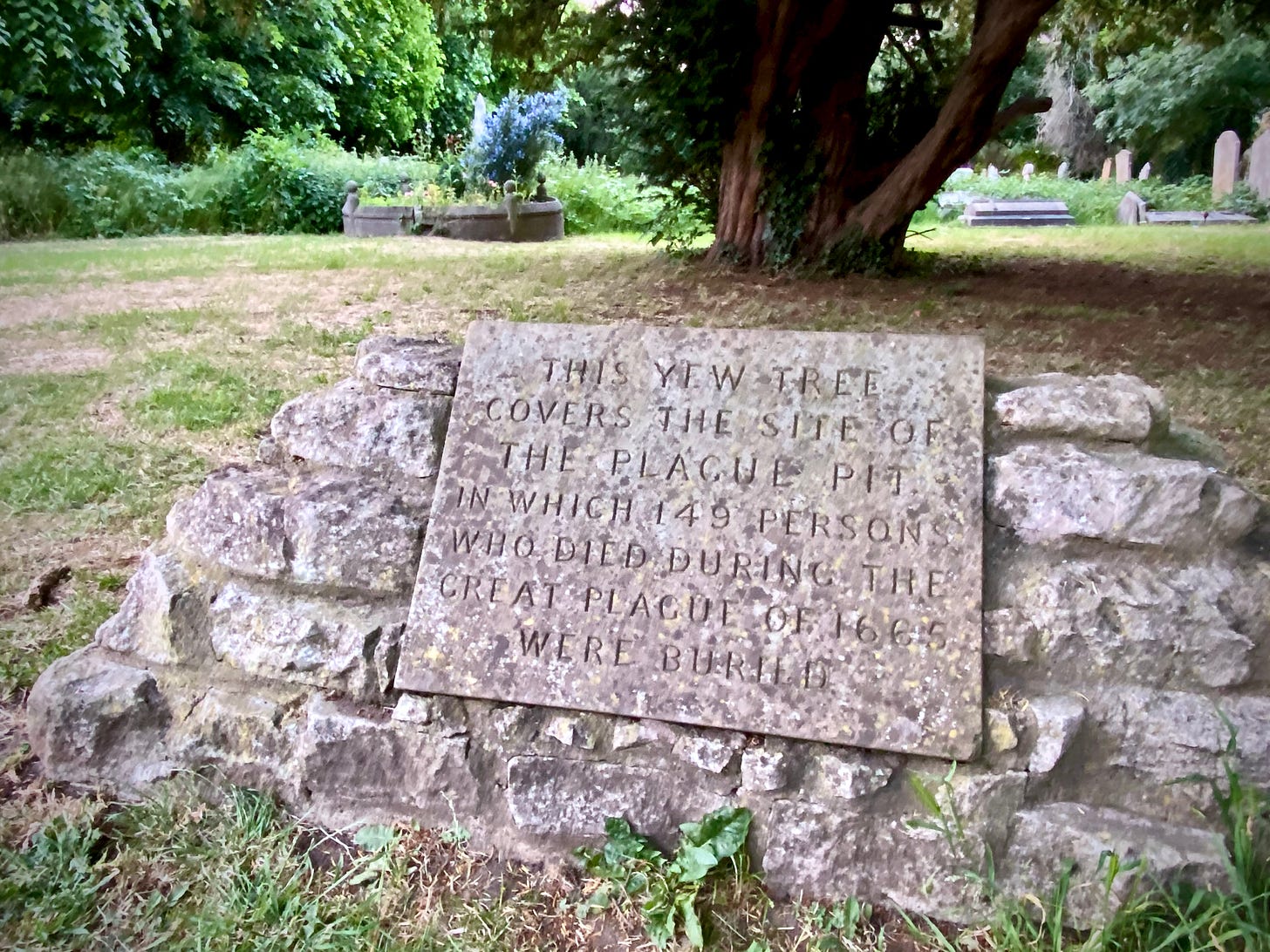

The often overlooked “plague pits” from almost 400 years prior became landmarks on my mental maps of Richmond, Hounslow, Hammersmith, and more.

They were more than macabre, historical curiosities worthy of Atlas Obscura. They were tangible markers of the city’s cyclical relationship with crisis. Walking to them was a form of urban archaeology, searching layers of history for inherent resilience.

I’m still immersed, but the venues and disruptions have changed.

From Urban to Proto-Urban Immersion

In the last year in New Mexico, my urban fabric has shifted to the north of Santa Fe—amid a political climate full of sudden and disruptive inconsistencies regardless of party allegiance. In another “this too shall pass moment,” I redefined my relationship with place. London’s familiar, walkable density has yielded to a new environment’s dispersed, more automobile-dependent spaces.

I refuse to concede a suburban, SUV-based retreat. Instead, I have adjusted to a fascination with different landscapes and now explore how urbanism, or its absence, shapes our perception of crisis and resilience.

A hand-me-down 1970 Ford Bronco was my first post-college starship. Its lineal Bronco Sport descendant is a tool for urban and proto-urban reconnaissance. For some reason, I have named it Trevor.

Trevor offers a way to access the interstitial spaces, the edges where the built environment dissolves into the natural, along the transects that legacy new urbanists champion. When snow and sand conspire, I can escape by turning a dial.

Trevor’s assured traction is more than mechanical. It provides a way to understand how visible and invisible infrastructure influences our daily experience.

Immersion in How Water Flows

A recent call with a friend in Singapore highlighted our contrasting awareness of how water flows. Her descriptions of evening runs along meticulously engineered parkland streams revealed a city optimized for control and amenity. It’s a vision of “engineered green,” a seamless integration of nature into the urban grid.

This conversation evoked familiar urban water paths: the Canal Saint-Martin in Paris, a transportation artery and public space, and the San Antonio Riverwalk, a carefully curated urban amenity designed to enhance the city’s appeal.

But here, with Trevor’s help, the landscape tells a different story than Venice and its imitators, London’s Little Venice or Annecy, the Venice of France. The arroyos, usually dry riverbeds, are not engineered for aesthetic or recreational purposes. They are a raw, unfiltered expression of the region’s hydrology, at most re-contoured in settled areas to keep floodwaters at bay.

Arroyos are flux spaces, shifting from arid channels to torrents in response to unpredictable rainfall. They display natural processes in contrast to the controlled environments of engineered waterways.

In winter, the arroyos present more as geology, their dry beds resembling glacial formations. They are windows to underlying topography, reminding us that water continues to shape and reshape the environment even in seemingly static landscapes, albeit in subtle, often imperceptible ways.

The conversation about Singapore’s often-engineered green and the dynamic, unpredictable arroyos would seem a far cry from London, where I wandered to seek reassurance from history about urban resilience.

Or not.

These explorations, forays into the urban periphery—whether on foot or with Trevor— are not obtuse distractions but a form of extended urban analysis. They allow us to understand how different built and natural landscapes shape our perception of risk and resilience.

What are the limitations of engineered solutions in adapting to natural processes?

How does our relationship with water, a critical urban resource, reflect our broader approach to resilience?

Engineered waterways represent a proactive, controlled approach that minimizes risk and maximizes amenities. On the other hand, observing the arroyos, I see a more reactive, adaptive approach that acknowledges the inherent unpredictability of natural systems.

Mapping Resilience

My pandemic walks and New Mexico explorations expose the underlying infrastructure of place, revealing the forces that shape what we see. They remind me that urban resilience transcends physical infrastructure and social and ecological systems.

The plague pits of London provided a historical framework for understanding urban crisis. In their raw, untamed form, the arroyos offer a contemporary lens for examining the relationship between engineered urbanity and nature. Far from the stillness of 2020, I’m reminded that places constantly adapt to the forces that shape them. We can find resilience in the landscape through careful observation and critical analysis.

Great photos, as always, Chuck!