About a year ago, with only a few subscribers, I started to write earnestly again about many aspects of understanding places, linking together various life experiences in the process.

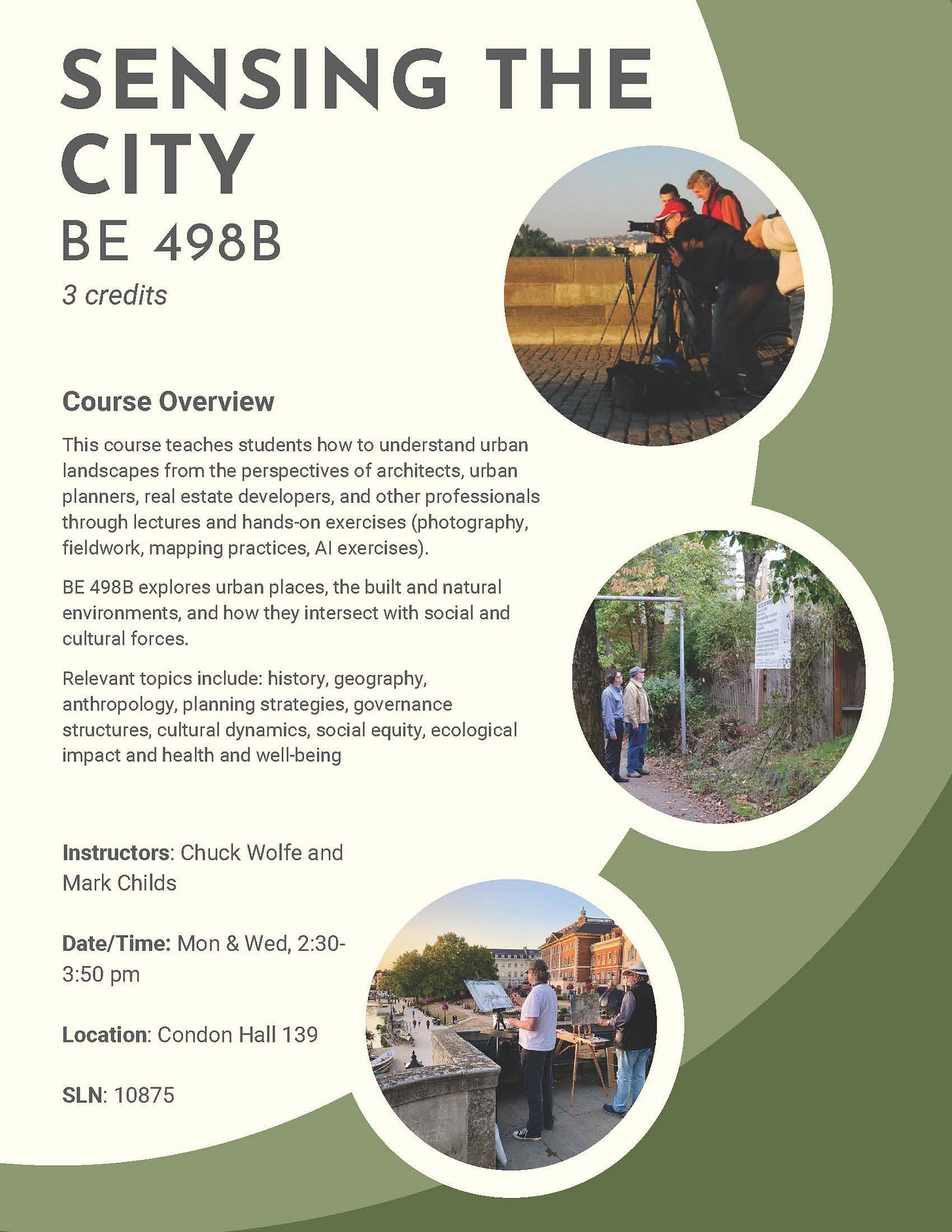

I’ve revised this post—one of the first I wrote—to reflect materials from my second book. It contains some first principles of observation, many of which will be discussed in a “Sensing the City” course that Mark Childs and I are slated to teach at the University of Washington in the Spring (the course poster appears at the end of this post).

In the era of Instagram, Threads, and other apps, documenting our “personal cities” has become second nature.

For some, this effort is as simple as using a smartphone and sharing one or more photographs on social media to document daily urban life. While on regular walks, others document potholes, land-use application notices, or various stages of new construction. Finally, for those who think beyond present boundaries, concerns about urban life depend on more poignant events far away, especially those in iconic, international urban places central to the interpretation of city life and urbanism.

For instance, in 21st-century Paris, London, Nice, and many other cities, the emotional reclaiming process after multiple terror events is part of the inevitable urban dynamic and our human capacity to rebuild. This dynamic often shows uniting rather than divisive themes in the urban landscape. As hinted in last year’s lighthearted, short post on avoiding “place excoriation,” visiting and photographing cities can stress these positive dynamics and inspire rebuilding and healing processes as needed.

In these instances, qualitative and interactive experiences and comparison seem more critical than assembling smart city “data points.” The qualitative and experiential also add personal dimensions to media representations of cities undergoing change or facing urban-planning challenges. For instance, visiting a place you have read or heard about—such as the changing face of East London—provides a firsthand reference for comparing with the impact of similar “gentrification” back home.

Another facet of photographing away from home comes from that indescribable human dance of history, people, and place that occurs when, while traveling, we like what we see. It is exciting when something resonates and invites a photograph—perhaps a notable urban space, a building, or a fragment of what was purposefully or inadvertently preserved. Sometimes, these experiences produce a simple, irrational gestalt: a sudden wish to live in the vacation venue for a year rather than a day . . . or at least to take the places home.

I’ve written several times about the Cinque Terre in northwest Italy, five towns now preserved as “artifacts” in a designated World Heritage Site, connected by footpath, rail, and water. Their magically photogenic amenities of street, square, and housing are, in reality, far more than facade-based touristic shells, dominated in the summer by strangers rejoicing in local wine and pesto, the absence of cars, and the wonders of a small-scale, interurban trek. As photo-centric urban diary subjects, the towns’ inspirational “we like what we see” elements—walkability, vibrant color, active waterfronts, and seamless interface with terraced landscapes— allow us to import the gift of urban ideas for potential implementation.

However, an excited, emotional response to an urban place while traveling does not always require an overseas journey to a place like the inspirational footpaths between the Cinque Terre towns. Recently, I was highly motivated to photograph the revitalization of downtown Detroit, which is now proceeding rapidly. On a visit to San Francisco in 2011, during a walk from the Financial District to Telegraph Hill, I encountered a series of urban diary scenes so evocative that they seemed at first staged for the camera. These views emphasized people, bright colors, and active settings; in contrast to “worse city” views, they show the “better city,” meaning the positive and dynamic side of urban perception and the full range of emotions away from home.

Urban Documentation Considerations Away from Home

Generally, consider the following when compiling photo-centric urban documentation, or “urban diaries,” while traveling:

1. If you are traveling to a place with a venerable urban history, look for inspirational examples that, if applied in context, might improve an urban space at home. For instance, the idea for New York’s High Line came first from Paris.

2. Beware of nostalgia when observing historic landmarks and places. It is unsurprising to be motivated or awestruck; the challenge is to think about why. What about seeing such a place, or otherwise sensing it, causes any particular reaction?

3. Use a camera shutter as a reflexive tool. Snap when feelings dictate a sensation; composition need not always be the initial goal.

4. Consider annotating why something seems significant in a text or voice note. This is very important when traveling, as it may not be easily possible to retrace steps or return to a place that seems significant to verify details about the location or circumstances of a given photo.

5. Guidebooks are helpful, but linear or literal travel is not necessarily the most authentic experience. Recall the role of the dérive and Situationist interpretation. If it’s safe, follow curiosity— sights and smells. On the other hand, be mindful. I once followed graffiti through narrow passages in Jerusalem’s Old City and ended up surrounded by a group of men in a courtyard. Even though the courtyard was “public,” I was promptly asked to leave.

6. Consider how juxtapositions seem different if traveling outside your home country. Private and public space, pavement surfaces, natural and built, transportation modes, and eras of construction on infrastructure and buildings, to name but a few, may all overlap in unaccustomed ways. It is often worthwhile to ponder why.

7. Looking at redevelopment projects reveals good focal points, as these projects tend to be emblematic of change yet can seamlessly blend with existing conditions. Reinvented urban space need not be controversial because it fails to honor existing fabric and context. Track responses carefully. In Nice, France, I am constantly aware of the blended interplay among pedestrians, buses, automobiles, and trams downtown in the post-tramway era, without the need for signage or traffic directions.

8. Follow basic human needs, such as starting urban diary themes. They will define what you see along the way. They may be as simple as the characteristics of where people live, where the less fortunate find a place to sleep, or the locations available for a trip to a store, restaurant, or café. Depending on distance, these factors will likely influence the chosen mode of transportation and the way crossings occur with other people’s paths. At home, similar choices may create journeys (and diaries) that look entirely different.

9. Center on people and, as noted, attempt to include them in photographs, even from afar. How we see people interacting with the physical environment and other factors will influence what we take away from exploration and observation.

10. Consider how light guides perception. An urban diary may assume a different mood depending on climate and color.

11. Emphasize—as I have in my new home of Santa Fe—the role of scale in the built environment and its appeal for street life. Many have written about how areas with diverse commercial street life and windows open to view (or other forms of soft edges) will create a different response than blank walls or other forms of limited accessibility.

Adapted from Wolfe, C.R., Seeing the Better City, (Island Press, 2017).