New Mexico may be for outlaw artists, but it’s also about places that memorialize conflicting and overlapping threads of American history. The same day that the New York Times championed the former, I investigated the latter at a place that remembers conflict as a solution to differences— and provides a metaphor for modern times.

Today’s political landscape and the daily buzz about swing-state polling sent me wandering to a nearby place that ended the Confederacy’s quest to abscond with the mineral-rich American West.

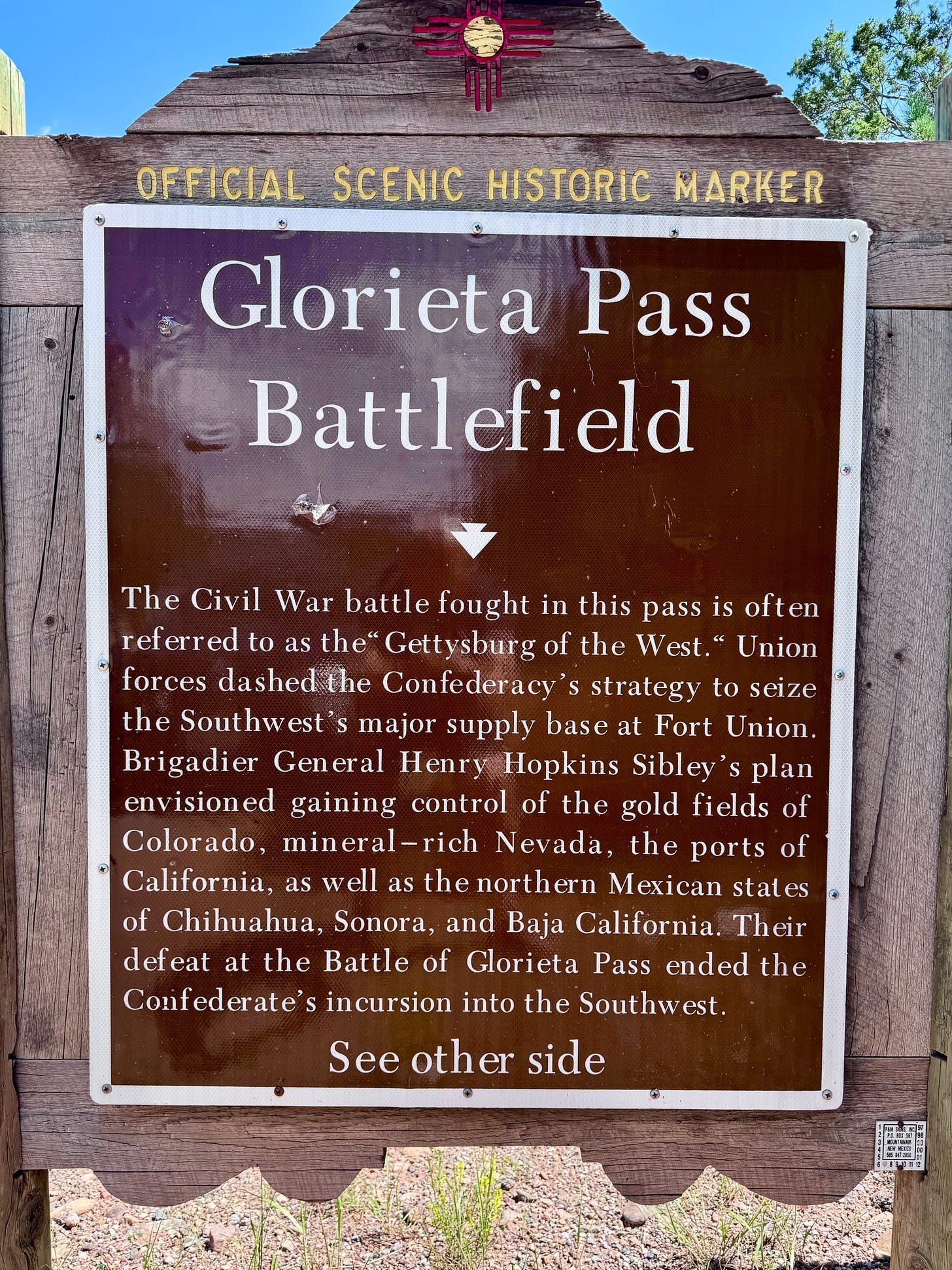

The Battle of Glorieta Pass, often referred to—over-dramatically, but it sounds good—as the “Gettysburg of the West,” took three days in March of 1862 and became a defining moment in the narrative of the American Civil War. As Thomas Edrington has noted:

[I]t is no wonder then that a fractured and excited nation took scant notice of a confrontation in far-off Territory of New Mexico, where a small force of Texans was wrestling with a federal command, mostly Coloradans, in a narrow defile about twenty-five miles east of Santa Fe… The day would come, however, when the Battle of Glorieta Pass would begin to take on a measure of importance…

Union forces under the command of Colonel John P. Slough engaged Confederate soldiers led by Colonel William R. Scurry. In a strategic masterstroke, the Union’s destruction of the Confederate supply line forced a retreat, effectively quashing Southern aspirations for dominance in the West.

Located near Pecos, New Mexico, the Glorieta Pass Battlefield offers few physical reminders of its storied past—just a modest remaining structure of Pigeon’s Ranch along Highway 50, and serpentine trails that meander through a landscape where Confederate troops once concealed themselves in arroyos at the base of Artillery Hill.

National Park Service materials, Edrington’s book, and another book by Don Alberts are full of Civil War-buff-lore of attacks, battle lines, howitzers and a strange wander by a young Texas sergeant surveying federal lines in a captured Union overcoat.

But that is mere backstory.

The place’s stillness today makes it easy to reflect on societal divisions. Interpretive signs and numbered National Park Service trail markers reveal—indirectly—the story of state’s rights, slavery, and economic disparity. Arguably their echoes persist in CNN v. Fox News, and a Presidential campaign.

Is it possible that such places are really roadmaps of the discord that still divides us?

I suggest that to visit this battlefield—which faced off insurgent, disgruntled recruits and the Union Army—is a poster child for understanding changed places and their subtle memories.

The absence of grand monuments or extensive ruins at Glorieta Pass frames the multidimensional reality that remains after conflict: the land, the literally buried memories, and lessons that we may have either absorbed or overlooked.

Places like Glorieta Pass are more than artifacts; more abstractly, they frame cycles of conflict and reconciliation. I came away from my Sunday visit thinking that it was a good, contemplative exercise of place, and a lesson about the toll of divisiveness rather than unity.

Chuck- This is a great photo-journal piece on lesser known parts. I love NM. And I love that photograph of the ditch where confederates hid. A very striking, if not visually affecting look at places with historical significance. Appreciate this. Hope you're well this week? Cheers, -Thalia